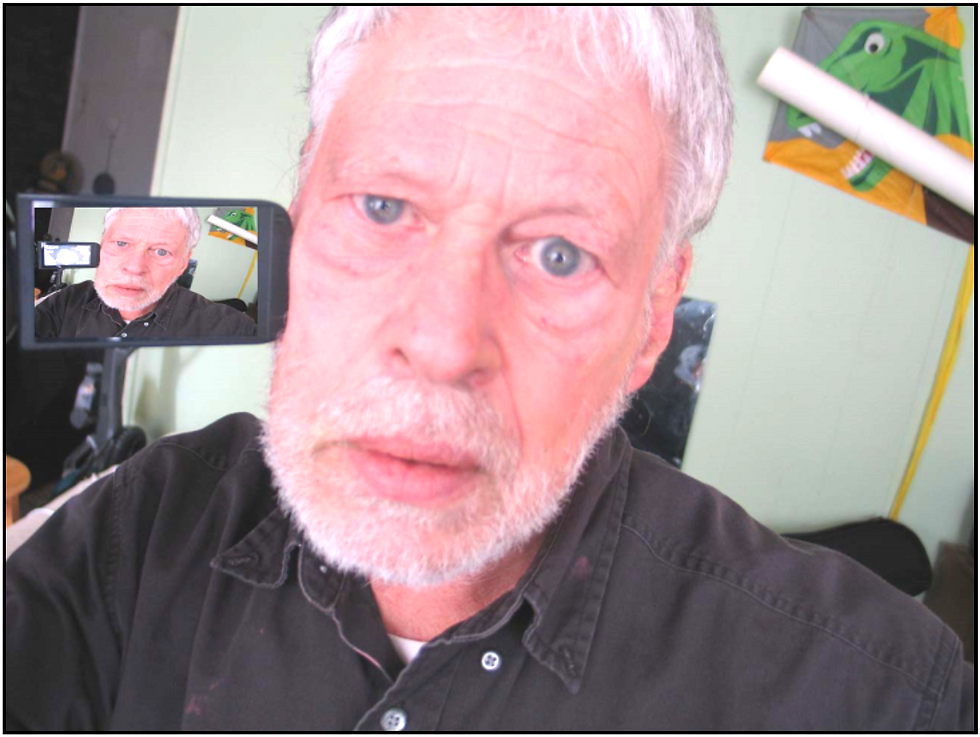

Rich Fishkin: Champion of Video Activism

- Neil Cosgrove

- May 10, 2016

- 3 min read

Rich Fishkin has been the videographer for many events sponsored by the Merton Center and other activist organizations over the years. He is convinced that these organizations could use video far more effectively than they have to further their missions and educate the public about issues.

His long list of suggestions includes partnering “with media organs, Pittsburgh Filmmakers, the Art Institute,” co-sponsoring “more screenings, festivals and competitions” and obtaining grants to “teach media literacy, use cell phones on police, do’s and don’ts, know your rights, help non-profits make and understand media, partner with other peace and justice groups to make and promote video.”

Such a program, Fishkin believes, would foster “a greater awareness of the role mass media propaganda plays in clothing the military industrial complex, turning war criminals into aristocrats and heroes.” Video brings immediacy and presence to activism, but activists themselves need to learn to “talk effectively, openly, honestly to the camera” and to prepare for video “with outline, photos, audio, music, tiles, all the elements needed for good production.” Activist organizations don’t do enough, he argues, to promote and distribute such video following production.

Fishkin’s convictions about the efficacy of video activism took root during his late ‘60s, early ‘70s involvement in the environmental movement, when he discovered how video “allows us to see and hear ourselves as others do.” As a young adult he became aware of childhood contradictions; being the son of a well-to-do lawyer living in the “best part of town” who was also the “only Jew in public school,” experiencing “lots of anti-Semitic bullying.” This awareness, combined with a growing passion for video production and concern about the environment, transformed him into an activist.

His first involvement with the Merton Center came about through that same environmental activism, at nuclear protests against Rockwell International and the Beaver Valley nuclear power plant in Shippingport. “Too bad I don’t still have those tapes,” he exclaims.

Perhaps his most arduous and frustrating struggle, one that lasted “maybe eight years,” was the debate in Pittsburgh over the cable franchise. “I tried to educate groups on the potential of public and educational channels,” but the city council “let cable corporations write the public policy we now have, designed public access to fail, with no educational access at all. …rich media, poor democracy.”

Fishkin remains proud of work he did on “homework hotline.” “You might say, what does this have to do with peace? Nothing, but it has everything to do with media reform, allowing kids to use television rather than being used by television—immediate, direct homework help which uses media as a classroom, extended into the living room, and promoting educational excellence. WQED/WQEX was not interested in the homework hotline model of television because they could not re-package and sell it. They wanted a cash register, not a classroom—a fraud.”

Fishkin’s connection to public access television is perhaps his most lasting, as at the age of 71 he continues, “as events/opportunities come up,” to make programs for Progressive Pittsburgh Notebook, which airs every Monday at 9 p.m. on PCTV 21. “I can’t stay away from this presidential election cycle.”

When asked if he is particularly proud of specific videos he has produced, he cites two: one focused on CIA whistleblower John Stockwell, specifically on CIA funding and organizing of narco-terrorist groups in Nicaragua and Kosovo. Spending two weeks in Serbia in August, 1999, six weeks after the bombing stopped, was Fishkin’s “witness to ‘war’ and through research I learned … the whole Kosovo war was triggered by false flag-staged violence and the propaganda machine that turns lies into truths, turns black into white, can make a devil look like an angel.” The second documented a lecture given by ecologist John Todd in 2002 at Duquesne University on the ecologically friendly treatment of sewage. This video has proven, over the years, to be the videographer’s most popular.

What shouldn’t be overlooked is the documentary value of Fishkin’s work and how it ensures that seemingly fleeting expressions of democratic commitment and progressive thought can be experienced again on sites like YouTube—the Regional Peace Convergence of 2003, the Occupy Pittsburgh movement of 2011, speeches by Bill McKibben, Martin Sheen, Jeremy Scahill, Barbara Lee. “Step back and begin to explore the pure process side of video,” admonishes Fishkin, “the interpersonal, sometimes deeply intimate feedback experience, and build individual and organizational strength from that base.”

Neil Cosgrove is a member of the NewPeople editorial collective and the Merton Center board.

Comments